Monthly Archives: March 2019

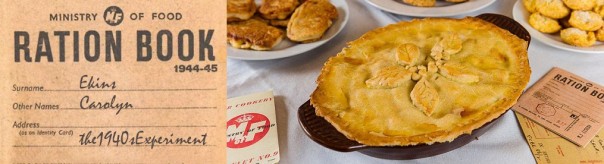

Home Front – Wartime Recipes (3)

We discussed rationing and we’ve discussed just how well our parents and grandparents ate – despite the rationing and time of war when all the “good” stuff was going overseas to the troops! So …. as promised, here are some more of the wonderful recipes from the 1940’s.

Please thank Carolyn on her website for putting these delicious meals on-line!

Recipe 61: Chocolate biscuits & chocolate spread

Recipe 62: Curried potatoes

Recipe 63: Vegetable pasties

Recipe 64: Wheatmeal pastry

Recipe 65: Homemade croutons

Recipe 66: Quick vegetable soup

Recipe 67: Fruit Shortcake

Recipe 68: Cheese potatoes

Recipe 69: Lentil sausages

Recipe 70: Root vegetable soup

Recipe 71: Sausage rolls

Recipe 72: Eggless ginger cake

Recipe 73: Mock duck

Recipe 74: Cheese sauce

Recipe 75: Duke pudding

Recipe 76: Potato scones

Recipe 77: Cheese, tomato and potato loaf/pie

Recipe 78: Bubble and squeak

Recipe 79: Belted leeks

Recipe 80: Lord Woolton Pie- Version 2

Recipe 81: Beef and prune hotpot

Recipe 82: Prune flan

Recipe 83: Butter making him-front style

Recipe 84: Mock apricot flan

Recipe 85: Corned beef with cabbage

Recipe 86: Oatmeal pastry

Recipe 87: Gingerbread men

Recipe 88: Carolyn’s mushroom gravy

Recipe 89: Jam sauce

Recipe 90: Brown Betty

Recipe 91: Middleton medley

Recipe 92: Rolled oat macaroons

Recipe 93: Anzac biscuits

Recipe 94: Beef or whalemeat hamburgers

Recipe 95: Lentil soup

Recipe 96: Welsh claypot loaves

Recipe 97: Chocolate oat cakes

Recipe 98: Wartime berry shortbread

Recipe 99: Oatmeal soup

Recipe 100: Mock marzipan

Click on images to enlarge.

###########################################################################################

Home Front Humor –

“Father, would not the best way to conduct the war be to let the editors of the newspaper take charge of it?”

############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

John Albert – So. Greensburg, PA; US Navy, WWII, air patrol

Phillip Baker – San Marcos, TX; US Army Pvt., 101st Airborne Division

George Carter – Crete, IL; US Navy, WWII & Korea, SeaBee

George Ebersohl – Madison, WI; US Army, WWII, ETO, medic

Hugh Ferris – Muncie, IN; US Army, WWII, ETO, 99th Infantry

Ambrose Lopez – CO; US Navy, WWII, PTO, USS Wake Island

Robert Parnell – Hampshire, ENG; British Army, WWII, ETO, 6th Airborne Division

James Swafford – Glencoe, AL; US Army, WWII, Purple Heart

Floyd Totten – Umatilla, FL; US Army, Korea, Co. B/187th RCT

Louis Ventura – Turlock, CA; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, 188th/11th Airborne Division

Current News – USS WASP – WWII Wreck Located

A port bow view of the ship shows her aflame and listing to starboard, 15 September 1942. Men on the flight deck desperately battle the spreading inferno. (U.S. Navy Photograph 80-G-16331, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Division, College Park, Md.)

The discovery of sunken wrecks seems to hold an eternal fascination. Although the quest to find them takes a huge amount of resources and technical skills, the quest goes on. Many searches have focused on the wrecks of warships lost during the Second World War. One of the most recent successes, despite many difficulties, was the discovery of USS Wasp (CV-7) deep in the Pacific Ocean.

The story of Wasp‘s end begins in September 1942. The aircraft carrier set out with 71 planes and a crew of more than 2,000 men on board to escort a convoy of US Marines to Guadalcanal, one of the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. In the middle of the afternoon, Wasp was hit by Japanese torpedoes which caused serious damage.

The worst part was that the torpedoes had hit the magazine, setting off a series of explosions. The fire quickly spread, and the ship was also taking on water from the torpedo damage. Soon it began to tilt, and oil and gasoline that had spilled were set ablaze on the water. Captain Sherman had no choice but to give the order to abandon ship.

Those who were most seriously injured were lowered into life rafts. Those who could not find a place in a life raft had no choice but to jump into the sea. There they held on to whatever debris they could to keep them afloat until they were rescued.

Captain Sherman commented later that the evacuation of the ship was remarkably orderly under the circumstances. He also noted that sailors had delayed their own escapes to ensure that their injured comrades were taken off the ship first.

The first torpedoes had been spotted at 2:44 PM. By 4 PM, once he was sure that all the survivors had been removed, Captain Sherman himself abandoned ship. In that short time, Wasp had been destroyed along with many of the aircraft it was carrying, and 193 men died.

Despite the danger involved, the destroyers which had accompanied Wasp carried out a remarkable rescue operation and managed to bring 1,469 survivors to safety.

The ship drifted on for four hours until orders were given that it should be scuttled. The destroyer USS Lansdowne came to the scene, and another volley of torpedoes eventually sank the ship into the depths of the Pacific Ocean.

The discovery of the wreck was largely due to the philanthropy of the late Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen had a lifelong enthusiasm for underwater exploration and a fascination with WWII wrecks. He provided the substantial sums required to fit out the Petrel exploration ship through his undersea exploration organization.

The quest to find Wasp looked likely to be one of their more difficult tasks. The wreck lay 2.5 miles down in an area known as an abyssal plane. There is no light and little animal life as well as massive pressure, making it one of the most inhospitable and inaccessible areas of the ocean.

Kraft and his team recalculated the possible location based on the distance between Wasp and the other two ships at the time of the torpedo attack. They realized that they needed to look much further south. It seemed that the navigator on Wasp had provided the most accurate location information after all.

The crew once again sent out drones to scan the area and on January 14, 12 days after their mission began, they located the wreck. Despite the massive damage, Wasp could be seen clearly in the underwater photographs, sitting upright on the seabed and surrounded by helmets and other debris that served as reminders of its dramatic history and tragic end.

The exact location of the wreck remains a closely guarded secret to avoid the risk of scavengers looking for valuable relics from the ship. There are no plans to attempt to raise the wreck, but its discovery has brought satisfaction to the few remaining Wasp survivors and their families.

Click on images to enlarge.

############################################################################################

Military Humor –

############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Chauncy Adams (101) – NZ; RNZ Army, WWII, 25th Wellington Battalion/3rd Echelon

James Baker – Farmersville, TX; US Army, WWII,PTO, Infantry, Chaplain (Ret. 20 y.)

Joseph Collette – Lancaster, OH; US Army, Afghanistan, 242 Ordnance/71st Explosive Ordnance Group, KIA

John Goodman – Birmingham, AL; US Navy, WWII, PTO

Willie Hartley – NC; US Army, Vietnam, 82nd Airborne Division

Richard Kasper – Brunswick, GA; US Army, WWII, PTO, Bronze Star

Will Lindsay – Cortez, CO; US Army, Afghanistan, Sgt., 2/10th Special Forces (Airborne), KIA

Stanley Mikuta – Cannonsburg, PA; WWII, PTO, Co. E/152nd Artillery/11th Airborne Division

Leonard Nitschke – Ashley, ND; US Army, Korea, Co. G/21/24th Infantry Division

Charles Whatmough – Pawtucket, RI; US Navy. WWII, PTO, Troop Transport cook

############################################################################################

Home Front – Big Timber, Montana

These two articles are from The Big Timber Pioneer newspaper, Thursday, August 30, 1945

Prisoners Hanged

Ft. Leavenworth Prison Cemetery; By Gorsedwa, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Fort Leavenworth, Kan., Aug. 25 – The Army Saturday hanged 7 German prisoners-of-war in the Fort Leavenworth disciplinary barracks for the murder of a fellow prisoner whom they had accused of being a traitor to the Reich.

All 7 went to the gallows after receiving last rites of the Roman Catholic Church. They were executed for killing Werner Dreschler at the Papago Park, Arizona prisoner of war camp, March 13, 1944.

The hangings took less than three hours. The executions brought to 14 the total number of Nazi POW’s executed at Ft. Leavenworth during the last few weeks.

The 7 went to the gallows without showing any signs of emotion. They had signed statements admitting their guilt. Their defense was that they had read in German newspapers that they should put to death any German who was a traitor. At their trial they said Dreschler had admitted giving information of military value to their captures.

***** ***** *****

Sgt. Nat Clark was on Pioneer Mining Mission

313th Wing B-29 Base, Tinian – One of the 6th Bomb Group fliers who participated in the pioneer mining mission to northern Korean waters on 11 July was SSgt. Nathaniel B. Clark, son of Mr. & Mrs. J.F. Clark, Big Timber, MT. it was revealed here today with the lifting of censorship rules. He is a left blister gunner and by war’s end had flown 29 combat missions in the war against Japan.

On the longest mission of the war, to deny the use of the eastern Korean ports to the already partially blockaded Japanese, Sgt. Clark explained that the crews were briefed to fly 3,500 statute miles to their mine fields just south of Russia, and back to Iwo Jima where they would have to land for fuel. Then it was still 725 miles back to the Tinian base.

The flight was planned to take 16½ hours which in itself was not out of the ordinary, but the length of time the full mine load would be carried was a record 10 hours and 35 minutes.

The job called for hair-splitting navigation, Midas-like use of the available gas, penetration of weather about which little is known and finally a precision radar mine-laying run over a port whose defenses and very contours were not too well known.

“We sweated that one out from our briefing one morning until we landed back on Tinian almost 24 hours later.” Sgt. Clark recalled.

One crew was forced to return to Okinawa because of engine trouble, but the other 5 on the pioneer flight landed within a few minutes of the briefed time. One landed at the exact briefed time. The closest call on gas was reported by the crew which landed with only 24 gallons left, scarcely enough to circle the field.

Click on images to enlarge.

##############################################################################################

Military Humor –

##############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Herman Brown – Virginia Beach, VA; US Army, WWII, ETO, 385/76th Division/ 3rd Army

Lester Burks – Willis, TX; US Army, Co. B/513/17th Airborne Division

Pedro ‘Pete’ Contreras – Breckenridge, OK; US Army, WWII, Korea & Vietnam, Lt.Col. (Ret. 30 y.)

Paul Jarret – Phoenix, AZ; US Army, WWII, ETO, Medical Corps, Bronze Star / US Air Force

John ‘Nick’ Kindred – Scarsdale, NY; US Navy, Lt.

James Lemmons – Portland, TN; US Army; Korea, HQ/187th RCT

Charles McCarry – Plainfield, MA; CIA, Cold War, undercover agent

Howard Rein Jr. – Philadelphia, PA; US Navy, WWII, PTO

Morton Siegel – Rye, NY; US Navy, WWII

Eldon Weehler – Loup City, NE; US Army Air Corps, WWII / US Air Force, Korea & Vietnam, Lt. Col. (Ret. 30 y.)

RAF in the Pacific War

After the fall of the Dutch East Indies, the British RAF contributed six squadrons to the Pacific Air War.

March 1941 allowed for the training of Allied pilots on U.S. soil and the formation of British Flying Training Schools. These unique establishments were owned by American operators, staffed with civilian instructors, but supervised by British flight officers. Each school, and there were seven located throughout the southern and southwestern United States, utilized RAF’s own training syllabus.

The aircraft were supplied by the U.S. Army Air Corps. Campuses were located in Terrell, Texas; Lancaster, California; Miami, Oklahoma; Mesa, Arizona; Clewiston, Florida; Ponca City, Oklahoma; and Sweetwater, Texas.

During the period of greatest threat to Australia in 1942, Winston Churchill agreed to release three squadrons of Spitfires from service in England. This included No. 54 squadron plus two RAAF expeditionary squadrons serving in Britain, Nos. 452 and 457. The Spitfire was at the time the premier Allied air defense fighter.

The squadrons arrived in Australia in October 1942 and were grouped as No. 1 Wing. They were assigned the defense of the Darwin area in January of 1943. The Wing remained in that role for the remainder of the war. In late 1943 two additional RAF Squadrons were formed in Australia, Nos. 548 and 549. These relieved the RAAF Spitfire squadrons for eventual duty with the 1st RAAF Tactical Air Force.

No. 618 Squadron, a Mosquito squadron armed with the Wallis bomb for anti-shipping missions was sent to the Pacific in late 1944 but never saw active service and was disbanded in June 1945.

In 1945 two Dakota squadrons, Nos. 238 and 243, were sent to the Pacific to provide support for the British Pacific Fleet.

The RAF’s No. 205 squadron, which was stationed in Ceylon, was responsible for air services between Ceylon and Australia during the war.

Raf ground crew & Singhalese lowering a Catalina of the 240th Squadron into the water, Red Hills Lake, Ceylon, 4 August 1945

Should the war have continued beyond VJ day, the RAF planned to send the “Tiger Force” to Okinawa to support operations against the Japanese home islands. As of 10 July 1945, the “Tiger Force” was planned to be composed of No. 5 (RAF) Group and No. 6 (RCAF) Group with 9 British, 8 Canadian, 2 Australian, and 1 New Zealand heavy bomber squadrons. The Force was to be supported by Pathfinder Squadron and a Photo/Weather Recon squadron from the RAF and 3 Transport and one air/sea rescue Squadrons from the RCAF.

Click on images to enlarge.

#############################################################################################

British Military Humor –

##############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Eileen Brown – London, ENG; WRAF, WWII, ETO

Irving Fenster – Tulsa, OK; US Navy, WWII

Tedd Holeman – Sugar City, ID; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, HQS/127 Engineers/11th Airborne Division

Stanley Jones – Shrewsbury, ENG; RAF, Chaplain

Daniel Lynn Jr. – Krupp, WA; US Army, WWII, ETO / Korea

Stanley Mellot – Grand John, CAN; RAF, WWII, navigator

James Raymond – Katanning, AUS, RAF, WWII

Paul Seifert Sr. – Bethlehem, PA; US Army, Korea, 82nd Airborne Division

David ‘Ken’ Thomas – Brown’s Bay, NZ; RAF # 1669434, WWII

Arthur Wan – Milwaukee, WI; US Navy, WWII, PTO

#############################################################################################

The Forgotten Fleet

Five British aircraft carriers at anchor at war’s end: HMS Indefatigable, Unicorn, Illustrious, Victorious, and Formidable

The Royal Navy was struggling to overcome its failure earlier in the Pacific, but during 1945, this forgotten fleet fought back dramatically to stand with the U.S. Navy against a storm of kamikaze attacks.

British naval operations in the Far East in World War II started badly and went downhill from there. Years of underfunding in defense meant that Britain simply did not have the means to defend its huge empire, and for 18 months prior to the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, it had stood alone against Nazi Germany.

Barracks at Tokishuma airfield, Shikoku Province, in the Japanese home islands, under attack by British naval aircraft, July 24, 1945. The planes were launched by HMS Victorious, Formidable, Indefatigable, and Implacable.

The Royal Navy was primarily committed to the Battle of the Atlantic, keeping open the all important sea lanes upon which the island nation’s survival depended. In the Far East, there were only token naval forces available to meet the Japanese attack, and in that part of the world Britannia’s claim to rule the ocean waves was immediately exposed for the empty rhetoric it had become.

The Pacific Ocean had never been a main operating area for the Royal Navy, so it was not geared or experienced for that sea’s vast distances in the way the U.S. Navy was; its vessels did not have the same cruising ranges and could not remain on station as long as the Yanks. So Task Force 57 started its operational life at a distinct disadvantage. This was compounded by having an inadequate supply fleet.

An auxiliary ship of Task Force 57 (center) refuels a British destroyer at sea. The Royal Navy struggled with logistics and resupply over the vast distances of the Pacific.

Because of the nature of the war it had been fighting in the Atlantic, the Royal Navy also had relatively little experience in large-scale carrier operations against land targets, which were the bread and butter of the U.S. Navy. For that reason, Task Force 57 practiced against targets in Sumatra when en route to the Pacific to gain experience and at the same time wreck some Japanese oil refineries.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the senior American naval officer in the Pacific, gave Task Force 57 a gracious welcome, signaling, “The British Carrier Task Force and attached units will increase our striking power and demonstrate our unity of purpose against Japan. The U.S. Pacific Fleet welcomes you.”

A British-marked Grumman TBM Avenger aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm, returning from an attack on Sakishima Gunto, flies above the HMS Indomitable in March 1945.

It was certainly not a token contribution. The combat elements of Task Force 57 at that time comprised four fleet carriers embarking 207 combat aircraft, two battleships, five cruisers, and 11 destroyers. There were also six escort aircraft carriers guarding the fleet train and ferrying replacement aircraft.

Commanding this formidable naval armament was Vice Admiral Sir Henry B.H. Rawlings. He and Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, at the helm of the American Fifth Fleet and directly in charge of all naval forces at Okinawa, worked well together.

By the end of April, the verdict on Task Force 57’s actions so far was generally considered “not bad.” The British were on a steep learning curve, getting used to a type of operation for which they were not properly equipped or trained. It had to refuel and resupply more frequently than the U.S. Navy and were still having serious problems with replenishment at sea.

An obsolescent Fairy Swordfish torpedo bomber approaches the HMS Victorious during operations. The ship was hit by three kamikazes during the Okinawa operation but survived.

In late May 1945, Task Force 57 broke off after 62 days at sea, returning to base to refit, resupply, and repair battle damage. Its first major missions of the Pacific War were over.

There would be more action to come, including Operation Inmate (June 14-16), involving air attacks on the main Japanese naval bastion at Truk in the western Caroline Islands, as well as raids on Japan itself in the run up to the planned invasion.

The British raids—both by air and shore bombardment—continued right up to August 15, 1945, and the Japanese surrender to the Allies; the second British task force, built around another four fleet carriers and one battleship squadron, arrived too late to take part in the fighting. By VJ Day, the Royal Navy Pacific Fleet had 80 principal warships (including nine large and nine escort aircraft carriers), 30 smaller combat vessels, and 29 submarines.

Click on images to enlarge.

##############################################################################################

British Military Humor –

##############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Gerald Ballard, Scranton, IA; US Coast Guard, WWII / USNR (Ret.)

Philip Corfman – Bowie, MD; US Navy, WWII, PTO / World Health Org. & FDA

Paul Gifford – Troy, NY; US Navy, WWII & Korea, corpsman, USS Shangri-La & Tranquility

Joe Jackson – Kent, WA; US Air Force, Vietnam, Medal of Honor

Charles Kettles – Ypsilanti, MI; US Army, Vietnam, Medal of Honor

Fernand Martin – Debden, CAN; Canadian Army, WWII, ETO

Gabriel Nasti – St. Augustine, FL; US Army, WWII, PTO, 20th Infantry/6th Division

Svend Nielsen – Copenhagen, DEN; Civilian, Danish Resistance, WWII, ETO

Jan-Michael Vincent – Hanford, CA; Army National Guard / beloved actor

Allen Wright (102) – Red Willow City, NE; US Army Air Corps, WWII, ETO, MSgt., Chemical Corps / USAR, Major (Ret. 31 y.)

##############################################################################################

OSS in Kunming, China

The OSS group that included Julia Child and her future husband Paul found themselves in a flood in mid-August 1945. But what they were encountering was nothing compared to the civilians. Chinese villages of mud huts were “melting like chocolate.” Farmers drowned in their own fields. As the flooding began to subside, Japan was hit with the second atomic bomb.

The incoming Russian soldiers only added to the Pandora’s box that was already opened in China. The OSS HQ in Kunming went into overdrive. Eight mercy missions were launched to protect the 20,000 American and Allied POW’s and about 15,000 civilian internees.

All the frantic preparations – for rescue operations, food and medical drops and evacuation – had to undertaken despite the weather conditions. Adding to the drama was the uncertain fate of the 6-man OSS team dispatched to Mukden in Manchuria to rescue General “Skinny” Wainwright, who endured capture along with his men since Corregidor in May 1942.

There was also evidence that other high-ranking Allied officials were held in the camp, such as General Arthur E. Percival, the former commander of Singapore.

On August 28, 1945, General Jonathan Wainwright steps down from a C-47 transport in Chunking, China, after three arduous years in a Japanese prison camp.

The OSS mercy missions were treated very badly. Officers were held up by Chinese soldiers and robbed of the arms and valuables. The mood in China was changing very quickly. Even in Chungking, the Chinese troops were becoming anti-foreign and uncooperative.

Word from Hanoi was that the OSS was beset with problems there as well. Thousands of still-armed Japanese were attempting to keep order in French Indochina. Paul Child told his brother he well expected a civil war to start there very soon. The French refused to recognize the Republic of Vietnam and worked with the British to push for “restoration of white supremacy in the Orient”.

The French were becoming more and more anti-American. They were using agents with stolen US uniforms to provoke brawls and cause disturbances. The British were dropping arms to French guerrilla forces to be used to put down the independence movement.

In Kunming, the streets were littered with red paper victory signs and exploded fireworks. Some of the signs were written in English and bore inscriptions reading, “Thank you, President Roosevelt and President Chiang!” and “Hooray for Final Glorious Victory!” Paper dragons 60-feet long whirled through alleyways, followed by civilians with flutes, gongs and drums.

The weeks that followed would be a letdown. Most of them were unprepared for the abrupt end to the war. Peace had brought a sudden vacuum. One day there was purpose and then – nothing had any meaning. The OSS would go back to their drab civilian lives.

Click on images to enlarge.

#############################################################################################

“Secret ?” Military Humor –

‘I don’t have any formal training, but I do own the complet boxed set of ‘Get Smart’ DVD’s.’

##############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Robert Dalton Jr. – Charlotte, NC; US Army, WWII, ETO, Bronze Star, Purple Heart

Clinton Daniel – Anderson, SC; US Army, WWII, PTO

Richard Farden – Rochester, NY; US Army Air Corps, WWII, ETO, 95th Bomber Group/8th Air Force

Murphy Jones Sr. – Baton Rouge, LA; US Air Force, Vietnam, Colonel, ‘Hanoi Hilton’ POW

Robert Haas – Toledo, OH; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, Co C/127 Engineers/11th Airborne Division

Dorothy Holmes – Colorado Springs, CO; US Air Force, Korea & Vietnam, Chief Master Sgt. (Ret. 30 y.)

Arnold ‘Pete’ Petersen – Centerville, UT; US Army, Vietnam, 101st Airborne Division, Purple Heart

Alfred Rodrigues Sr. (99) – HI; US Navy, WWII, Pearl Harbor survivor

Tito Squeo – Molfetta, ITA; US Merchant Marines, WWII, diesel engineer

Joseph Wait – Atlanta, GA; US Navy, WWII, PTO, pilot

##############################################################################################

Soviet Invasion – August 1945

Stalin’s simple purpose for declaring war against Japan was for territorial gain, for which he was prepared to pay heavily. Before launching their assault in Manchuria, the Soviets made provision for 540,000 casualties, including 160,000 dead. This was a forecast almost certainly founded upon an assessment of Japanese strength, similar to what the US estimated for a landing at Kyushu.

Since 1941, Stalin had maintained larger forces on the Manchurian border than the Western Allies ever knew about. In the summer of 1945, he reinforced strongly, to create a mass sufficient to bury the Japanese. Three thousand locomotives labored along the thin Trans-Siberian railway. Men, tanks and matérial made a month-long trek from eastern Europe.

MANCHURIA: RED ARMY, 1945.

A Soviet marine waving the ensign of the Soviet navy as Soviet airplanes fly overhead after the victory over the Japanese occupation troops in Port Arthur, South Manchuria. Picture taken August 1945 by Yevgeni Khaldei.

Moscow was determined to disguise this migration. Soldiers were ordered to remove their medals and paint their guns with “On To Berlin” slogans. But train stations were often lined with locals, yelling support for them to fight the Japanese. So much for secrecy.

Some of the men thought they were returning home. After 4 years of war, they were dismayed to be continuing on. “Myself, I couldn’t help thinking what a pity it would be to die in a little war after surviving a big one,” said Oleg Smirnov.

After traveling 6,000 miles from Europe, some units marched the last 200 miles through the treeless Mongolian desert. “I’d taken part in plenty of offenses, but I’d never seen a build-up like this one,” said one soldier. “Trains arriving one after another… Even the sky was crowded: there were always bombers, sturmoviks, transports overhead.”

Machine-gunner Anatoly Silov found himself at a wayside station where he was presented with 5 mechanics, 130 raw recruits and crates containing 260 Studebaker, Chevrolet and Dodge trucks he was ordered to assemble. “As the infantry marched, the earth smelt not of sagebrush but of petrol.” Most of the men lost their appetites for food and cigarettes, caring only about thirst.”

By early August, 136,000 railway cars had transferred eastwards of a million men, 100,000 trucks, 410 million rounds of small-arms ammo, and 3.2 million shells. Even firewood had to be cut in forests and shipped 400 miles. “Many of the guys rubbished the Americans for wanting other people to do their fighting,” said Oleg Smirnov.

As troops approached the frontier, their camouflage and deception schemes were used to mask their movements. Generals traveled under false names. These veterans of the Eastern front were up against 713,724 of the so-called Manchukuo Army of which 170,000 were local Chinese collaborators. The Japanese weapons were totally outclassed by the Soviets’. Many mortars were homemade, some bayonets were forged from the springs of discarded vehicles.

MANCHURIA: RED ARMY, 1945.

Soviet troops in Harbin in Manchuria, after their victory over the Japanese occupation troops, 1945.

On 8 August 1945, the Soviet troops were told, “The time has come to erase the black stain of history from out homeland….” To achieve surprise, the Soviets denied themselves air reconnaissance. The 15th Army crossed the Amur River with the aid of a makeshift flotilla of commercial steamships, barges and pontoons. Gunboats dueled with the shore batteries. One Soviet armored brigade made it 62 miles into Manchuria before the rear units made it ashore.

The Japanese Guandong Army had suffered a tactical surprise by overwhelming forces. On the morning of 9 August, the Japanese commander, Otozo Yamada, called the Manchukuo Emperor, Pu Yi. Yamada’s assertions of confidence in victory were somewhat discredited by the sudden scream of air raid sirens and the concussions of Russian bombs. Pu Yi, a hypochondriac prey to superstition and prone to tears, an immature creature at 39, heartless in ruling his people, now was extremely paranoid and terrified of being killed.

Click on images to enlarge.

##############################################################################################

(Russian ?) Military Humor –

YOU get the CAR where IT needs to be!!

##############################################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Mason Ashby – Floyds Knoles, IN, US Army, WWII, PTO

Donald Catron – Logan, UT; US Merchant Marines, WWII / US Army, 11th Airborne Division

Arthur Dappolonio – Boston, MA; US Army Air Corps, WWII

William Gutmann – KY; US Navy, WWII, PTO, USS Siboney, medic

Henry James – Rolla, ND; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, SSgt., 3 Bronze Stars, Purple Heart

James Knight – Longview, WA; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, 11th Airborne Division

Robert Lundberg – Erie, PA; US Army Air Corps, WWII,ETO, P-47 mechanic

James Petrie – Rangiora, NZ; 2NZEF # 19483, WWII, ETO, Pvt.

Roy Theodore – Lestock, CAN; Crash Rescue Firefighter, WWII, ETO

Eugene Williams – Washington D.C.; US Navy, WWII, ETO, LST, Purple Heart

##############################################################################################