Monthly Archives: March 2024

THE STRANGE NAVY THAT SHIPPED MILLIONS OF JAPANESE HOME

When Japan formally surrendered on board the USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945, there still were seven million Japanese soldiers and civilians scattered throughout the Pacific and Asia with no way of returning home. The Allies had so devastated Japanese shipping during the war that few transports remained. There were some grumblings among U.S. officials who thought that it was Japan’s problem to rectify, but it was quickly recognized that after suffering under Japanese occupation for years, countries such as China and the Philippines should be relieved of the burden of stranded Japanese troops. There was also a need to return the million Chinese and Koreans who had been taken by the Japanese for slave labor.

By mid-September, a plan to repatriate Japanese personnel and revive the Japanese economy began to take shape. The U.S. Navy established the Shipping Control Authority, Japanese Merchant Marine and the Japanese Repatriation Group, known collectively as SCAJAP, under the Commander, Naval Forces, Far East (COMNAVFE). RADM D. B. Beary commanded SCAJAP with RADM Charles “Swede” Momsen serving as his chief of staff. SCAJAP developed regulations for Japanese shipping rights, laws of the sea, and safety rules. SCAJAP then assembled a fleet to transport cargo and another fleet to be used for the repatriation operation.

IJN Hosho

To hasten repatriation, SCAJAP gave Japan 85 LSTs and 100 Liberty ships that had been slated for decommissioning. Because the plan called for the ships to be operated by Japanese crews, all the instruments and hatches had to be remarked with Kanji. SCAJAP also repurposed any seaworthy vessel it could, including warships, for the mass repatriation effort. The Hōshō and Katsuragi, among the few Japanese carriers to survive the war, were given new roles as passenger transports, as were destroyers such as the Yoizuki. The ocean liner Hikawa Maru, which had been converted into a hospital ship, was used to gather thousands of men at a time. The fleet of castoffs eventually grew to about 400 vessels. The Japanese government was responsible for providing the crew with all food and supplies. Fuel had to be bought through U.S. authorities.

Because the rising sun flag was abolished following the surrender, the ships of SCAJAP were given their own flags. Japanese-owned ships with Japanese crews flew a blue and red pennant modified from international flag signal code for “Echo.” American-owned ships with Japanese crews flew a flag of red and green triangles based on the signal code for “Oscar.”

Unsurprisingly, many American servicemen who were waiting to be shipped back to the United States were not happy with the effort. They complained that their return was being delayed because resources were being used to accommodate the same Japanese whom they’d been fighting only weeks earlier. Officials explained that Asia would not recover without immediate repatriation, resulting in more Americans having to stay longer to stabilize the region.

The operation was conducted quickly and efficiently with only a few incidents. One fully laden ship sank after hitting a mine near China but only 20 of the 4,300 passengers were lost. In another incident, there was outrage when the public learned of the appalling conditions of a ship that was overcrowded with women and children being returned to Taiwan. Korean refugees on another ship almost mutinied against the Japanese crew because of what they believed was inhumane treatment.

The removal of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians on Taiwan also was problematic because many had lived on the island their entire lives and considered it their true home. Most wanted to remain, but the Chinese announced that they intended to use any Japanese on the island as slave labor. Against U.S. objections, the Chinese also created ways to extort the Japanese being repatriated by charging them for the transportation and inoculations that the United States was providing for free.

SCAJAP ships also encountered bitter feelings that remained from the war. When a couple of Japanese-operated ships pulled into Hawaii for repairs, the crew was not permitted to go ashore.

The repatriation effort was conducted at a remarkable speed. It was initially estimated that the operation would take until July 1947 to complete, but In March 1946 Momsen projected that the repatriation effort would be complete by that May, with the exception of the 1,700,000 Japanese who were being held by the Soviets. SCAJAP earned additional praise from the Japanese government for returning the exhumed remains of thousands of Japanese war dead from far-flung places.

SCAJAP’s repatriation operation was an extraordinary logistical achievement that played a significant role in the postwar recovery of Asia. After completion of the operation, SCAJAP ships would soon be called upon to transport men and equipment to Korea, providing crucial support in the amphibious operations at Inchon and Wonsan.

The signing of the Treaty of San Francisco on 8 September 1951 meant that Japanese ships could again fly the rising sun and operate under policies developed by the Japanese government. On 1 April 1952, SCAJAP was dissolved. Many Japanese-crewed ships remained in the service of Military Sea Transportation Services, drawing the ire of U.S. maritime unions, which charged that the practice was depriving Americans of jobs.

Info from: U.S. Naval Institute

##############################################################################

Military Humor –

##############################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

John Burson – Atlanta, GA; US Army, WWII, ETO, Bronze Star

Dan Corson – Middletown, OH; US Army Air Corps, WWII, ETO, Lt., 401 BS/91BG/ *th Air Force, B-17 co-pilot, KIA (FRA)

Robert Cross (100) – Yorkton, CAN; RC Air Force, WWII, ETO, mechanic

Charles Crumlett – Streamwood, IL; US Air Force, SSgt., weapons load chief, 90th Fighter Generation Squadron, KWS (Alaska)

Roland A. Hall – Hurricane, UT; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, 188/11th Airborne Division, Bronze Star

Richard J. Kasten – Kalamazoo, MI; US Army Air Corps, WWII, ETO, 1stLt., B-24 navigator, 68BS/44BG, KIA (FRA)

Matthew Langianese (103) – Moab, UT; US Army, WWII, ETO / Korea

Gerald W. Miller Vienna, VA; US Army, WWII, cartographer / US Navy, Korea

Ira “Frank” Moseley (101) – Conyers, GA; US Army, WWII, ETO / US Air Force

William L. Reichow – Decorah, IA; US Army, Sgt., 11th Airborne Division

Leroy J. Schoenemann (101) – Lyons, TX; US Army Air Corps, WWII, PTO, pilot, 64th Troop Carrier Wing

Brooks Winfield – San Rafael, CA; US Navy, WWII, PTO, Radioman, USS Oklahoma, KIA (Pearl Harbor, HI)

##############################################################################

##############################################################################

The History of V-Mail

Jeanne, who pens the excellent blog, “Everyone Has A Story” has this historical and interesting article from WWII…

Joy Neal Kidney also did a post on V-Mail…

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

Chester W. Nimitz : “Every Man’s Admiral”

(excerpts from “OUR NAVY” magazine, 1 September 1946)

He hailed from Fredericksburg, Texas, with a sea-faring family history. It seemed natural he would choose a Navy career, but in high school, his friends made plans for the Army. Chester decided he would compete with them for West Point.

When Nimitz became eligible to take the exam, he learned there were no more appointments available in his district, except for Annapolis. The winner of a competitive examination would land him that assignment. He entered in 1901 with Royal Ingersoll and William F. Halsey, Jr.

In his first year, he showed up at the boat dock, his 150 pounds barely filling his gym suit, and tried to get a place on the boat crew. The coach thought he was a bit small, but Nimitz said, “Give me a chance.” He got that chance and became the stroke oar in the 4th crew. They did so well, the Texan was promoted to the 3rd crew that consequently kept winning. Out-weighed by 35lbs., Chester would stroke the seven men in the first boat.

At 23-years old at the Asiatic Station, he impressed his superiors as an officer fit for submarine service. With his executive abilities, remarkable memory and exceptional patience, he arrived at the 1st Submarine Flotilla for his training.

The first sub Nimitz took command of was only the second one accepted by the Navy, the Plunger. Not even named for a fish, he called it “a cross between a Jules Verne fantasy and a whale.” He then proceeded to other classes of underwater craft.

One day in March 1912, while on the Skipjack, W.J. Walsh F2c was washed overboard. He couldn’t swim. Nimitz was the first to dive into the water and reach him before he went under, as they were both being carried away in the tide. This high character and confidence his men felt here, followed Chester Nimitz through all his commands.

In WWI, he served as Chief of Staff to Admiral Samuel S. Robinson, commander of the U.S. Submarine Forces. Because of his rank, he soon found himself in the surface fleet and he continued to climb.

When Nimitz arrived on the still smoldering Pearl Harbor to take over command of the Pacific Fleet, the CinCPac staff that had served under Admiral Kimmel nervously presumed the ever-efficient Nimitz to hand them transfer orders. Instead, he said, “I did not come here to mete out punishment. I know what you men are expecting me to say. I should be honored to have the entire staff stay with me and work until victory is ours.”

He proved he could pick out top commanders by choosing Spruance to take over Halsey’s ailing Task Force. and Comdr. Eugene Fluckey, also an ex-skipper of the submarine Barb, for his personal aide. From there we know of the exploits of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz during WWII.

For a man who had no more than the average youth’s advantages, I believe we can all agree he had done quite well. Fleet Admiral Nimitz passed away 20 February 1966, 4 days before his 81st birthday.

This magazine was supplied by Jeanne Salaco, blog “everyone has a story to tell”. Thank you once again, Jeanne!

#############################################################################

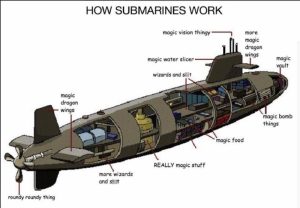

Military Humor –

##############################################################################

Farewell Salutes –

Richard Berky – Bluffton, OH; US Army, WWII, ETO

William O. Chase – Sacramento, CA; US Army, Korea

John E. Deist III – Sterling, KS; US Army, Iraq, Sgt. Major (Ret. 21 y.), Bronze Star

Frank A. Kulow Jr. – Bailey, CO; US Coast Guard, WWII

Wrilshxer Mendoza – CA; US Air Force, Afghanistan, 82nd Airborne Division, (Ret. 22 y.)

I.G. Nelson – Plymouth, IA; US Army Air Corps, Japanese Occupation, 11th Airborne Division

Robert Oxman – Natick, MA; US Army Air Corps, WWII

Amelia Pagel – Temple, TX; Civilian, WWII, Lackland Air Force Base, aircraft repair

Robert T. Shultz – Arlington, VA; US Navy, Vietnam, Annapolis Class of ’50, Cmdr. (Ret. 26 y.), Bronze Star

Jack G. Thomas – Kalispell, MT; US Navy, Vietnam, fighter pilot / NV National Guard, Colonel

Marguerite Wood – NJ; Women’s Royal Naval Service, WWII

##########################################################################

MONDAY?! Uh-oh, are they looking at me now?

##############################################################################